After three seasons of enduring a spin-off that never quite matched its predecessor, Sex and the City fans can finally exhale with news of its official end.

There comes a moment in any revival when the weight of expectations becomes too heavy, and And Just Like That might have reached that turning point. As showrunner Michael Patrick King revealed, the Sex and the City spin‑off will conclude after its third season with a two‑part finale slated for August 14, 2025. For many fans who’ve lingered in hope, this moment, though tinged with sadness, is also a quiet relief.

This series often basked in the sheen of designer lifestyles and elite social circles, but the emotional truths surfaced in moments like Carrie wrestling with her long‑distance relationship with Aidan. Such glimpses proved the show’s potential to tap into authentic, midlife intimacy. Still, many moments skirted substance, leaning instead into caricature: resigned matrons defined by cosmetic anxieties or socially sensitive clichés.

It’s not just And Just Like That. Across the board, Hollywood struggles to write midlife women with depth, complexity, and truth. A decade-long analysis revealed that characters aged 50 and up occupy less than 25% of screen roles, and even within that small percentage, women are routinely underrepresented. Too often, they’re shuffled into supporting roles, stereotyped as meddling mothers, eccentric neighbors, or corporate ice queens. Rarely are they granted the layered humanity, romance, and inner life that their male counterparts enjoy well past middle age.

And Just Like That, with its built-in fan base and cultural legacy, was perfectly positioned to break this cycle. Instead, it often echoed the very shortcomings it could have dismantled.

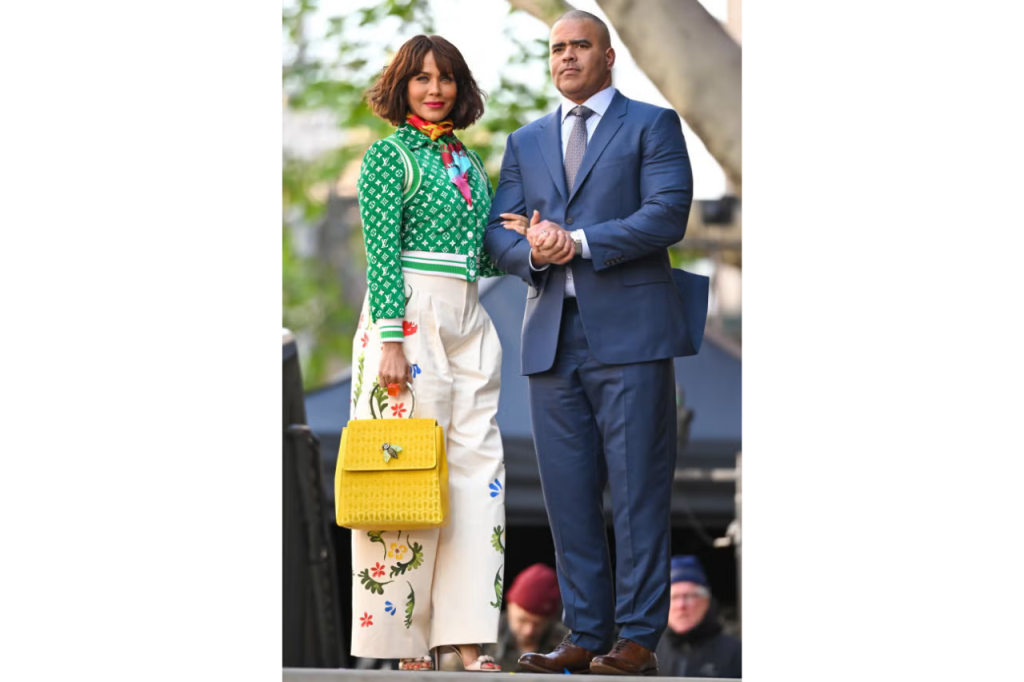

Opting for glossy distractions and underdeveloped storylines. Charlotte’s arcs frequently revolved around social status anxieties; Miranda became a caricature in pursuit of relevance; Carrie became a “pick me,” accepting crumbs from Aidan like an immature teen. And then there’s Sema, one of the few characters with the potential to bring fresh energy, handed one of the most tired plotlines in the book: falling for a much younger man who was far from her type and tax bracket. It played like a midlife fantasy drafted in a writer’s room unwilling to imagine more complex, surprising possibilities for a glamorous, fiercely independent woman.

By the time the writers seemed to grasp that viewers wanted richer, more grounded storytelling, hinted at in rare scenes like Carrie confronting the unraveling of that relationship or Lisa wrestling with her creative identity, they had already lost the trust and attention of their core audience.

This gap in representation isn’t about giving midlife women “their turn”; it’s about reflecting reality. Women over 50 are leading companies, falling in love, raising children and grandchildren, ending marriages, starting businesses, and confronting mortality, sometimes all in the same week. Yet on screen, they’re often written as either exhausted matriarchs or comedic relief.

The absence of nuanced portrayals reinforces a damaging cultural message: that a woman’s inner life peaks in her twenties and thirties, and after that, it’s background noise.

Meanwhile, male actors continue to be cast as romantic leads into their seventies, often opposite partners young enough to be their daughters. It’s not simply an imbalance; it’s a distortion.

And Just Like That could have been a blueprint for a new era of television, one where midlife women are shown as fully dimensional, with the same capacity for passion, ambition, reinvention, and vulnerability as their younger selves.

It could have sparked a ripple effect, encouraging other shows to follow suit. But by leaning on familiar tropes and avoiding deeper waters, it left that cultural door only half-open.

Yes, it gave viewers nostalgia and occasional emotional highs, but it never fully embraced the complexity of the demographic it claimed to center.

The only true bright spot was the thoughtful care given to Lisa’s character. From the curated design and decor of her home, rooted in African American heritage and pride, to the authentic way her storylines unfolded, Lisa felt like a fully realized woman rather than a sketch. Her arc exploring the possibility of an unexpected pregnancy in midlife was especially resonant.

It captured the internal tug-of-war so many women face when their children are nearly grown: the collision of shifting identities, altered life plans, and the stark reality of how another child would reshape everything from career ambitions to personal freedom.

It was one of the few moments where the series honored the complexity, vulnerability, and layered decision-making that defines this stage of life.

Lisa’s story proved that And Just Like That had the capacity to tell nuanced, deeply human narratives about women in midlife. If the same level of care and cultural specificity had been applied to Carrie, Miranda, and Charlotte, the series could have redefined what it means to age on television.

Miranda’s exploration of her sexuality could have been less cringeworthy and more emotionally layered, focusing on the vulnerability, excitement, and uncertainty of rediscovering oneself in midlife, rather than reducing her to a chaotic bundle of quirks and bad decisions.

Charlotte’s arcs could have leaned into the quiet reckoning of realizing that “having it all” doesn’t shield you from loss, boredom, or the need for reinvention. A storyline exploring how a woman who’s always played by society’s rules recalibrates when those rules no longer serve her could have been both relatable and revealing.

And Carrie, arguably the heartbeat of the franchise, could have evolved into a character who values her worth, someone learning to navigate this season of life alone, but this time by choice. Instead of floating through dinner parties, she could have confronted the emotional costs of chasing an old love, and what it means to build a full life on her own terms in her fifties.

Instead, Lisa became the exception, the reminder of what the show could have been if all four women were treated as multidimensional protagonists rather than a mix of nostalgia bait and missed opportunities.

Watching And Just Like That wasn’t passive; it was an exercise in hope. Hope that Carrie’s relationships could resonate beyond fashion, that Miranda and Charlotte could evolve in ways that felt authentic, complex, and unapologetically real, that midlife didn’t mean invisibility

Hollywood at large remains a flawed storyteller when it comes to midlife women, crowded out by ageism, underwritten, and too often overshadowed by youth. But the series’ finale marks a moment of clarity: a reminder that audiences are ready for stories that prioritize emotional depth, age authenticity, and cultural specificity.

In closing now, the spin-off doesn’t feel like a total failure; it feels like proof of concept. Proof that when a show commits to portraying midlife women with nuance, as it occasionally did with Lisa, it connects. And perhaps, in its final bow, it makes space for bolder, braver, and more truthful portraits of women in midlife, and the audience that’s been waiting far too long for them.